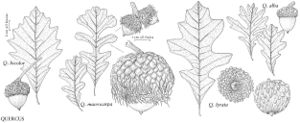

Quercus alba

Sp. Pl. 2: 996. 1753.

Trees, deciduous, to 25 m. Bark light gray, scaly. Twigs green or reddish, becoming gray, 2-3 (-4) mm diam., initially pubescent, soon glabrous. Buds dark reddish-brown, ovoid, ca. 3 mm, apex obtuse, glabrous. Leaves: petiole (4-) 10-25 (-30) mm. Leaf-blade obovate to narrowly elliptic or narrowly obovate, (79-) 120-180 (-230) × (40-) 70-110 (-165) mm, base narrowly cuneate to acute, margins moderately to deeply lobed, lobes often narrow, rounded distally, sinuses extending 1/3-7/8 distance to midrib, secondary-veins arched, divergent, (3-) 5-7 on each side, apex broadly rounded or ovate; surfaces abaxially light green, with numerous whitish or reddish erect hairs, these quickly shed as leaf expands, adaxially light gray-green, dull or glossy. Acorns 1-3, subsessile or on peduncle to 25 (-50) mm; cup hemispheric, enclosing 1/4 nut, scales closely appressed, finely grayish tomentose; nut light-brown, ovoid-ellipsoid or oblong, (12-) 15-21 (-25) × 9-18 mm, glabrous. Cotyledons distinct. 2n = 24.

Phenology: Flowering in spring.

Habitat: Moist to fairly dry, deciduous forests usually on deeper, well-drained loams, also on thin soils on dry upland slopes, sometimes on barrens

Elevation: 0-1600 m

Distribution

Ont., Que., Ala., Ark., Conn., Del., Fla., Ga., Ill., Ind., Kans., Ky., La., Maine, Md., Mass., Mich., Minn., Miss., Mo., Nebr., N.H., N.J., N.Y., N.C., Ohio, Okla., Pa., R.I., S.C., Tenn., Tex., Vt., Va., W.Va., Wis.

Discussion

Considerable variation in depth of lobing occurs in the leaves of Quercus alba (M. J. Baranski 1975; J. W. Hardin 1975); the species is easily distinguished from others, however, by the light gray-green, glabrous mature leaves and cuneate leaf bases.

In the past Quercus alba was considered to be the source of the finest and most durable oak lumber in America for furniture and shipbuilding. Now it has been replaced almost entirely in commerce by various species of eastern red oak (e.g., Q. rubra, Q. velutina, and Q. falcata) that are more common and have faster growth and greater yields. These red oaks also lack tyloses and therefore are more suited to pressure treating with preservatives, even though they are less decay-resistant without treatment.

Medicinally, Quercus alba was used by Native Americans to treat diarrhea, indigestion, chronic dysentery, mouth sores, chapped skin, asthma, milky urine, rheumatism, coughs, sore throat, consumption, bleeding piles, and muscle aches, as an antiseptic, and emetic, and a wash for chills and fevers, to bring up phlegm, as a witchcraft medicine, and as a psychological aid (D. E. Moerman 1986).

Numerous hybrids between Quercus alba and other species of white oak have been reported, and some have been named. J. W. Hardin (1975) reviewed the hybrids of Quercus alba. Nothospecies names based on putative hybrids involving Q. alba include: Q. ×beadlei Trelease (= Q. alba × prinus), Q. ×bebbiana Schneider (= Q. alba × macrocarpa), Q. ×bimundorum E. J. Palmer (= Q. alba × robur), Q. ×deami Trelease (= Q. alba × muhlenbergii), Q. ×faxoni Trelease (= Q. alba × prinoides), Q. ×jackiana Schneider (= Q. alba × bicolor), and Q. ×saulei Schneider (= Q. alba × montana).

Selected References

None.