Vines [shrubs, trees], perennial [rarely annual], woody or herbaceous, with [without] tendrils; axils with multiple axillary buds, primary axillary bud often developing into inflorescence or tendril; bark smooth to rough or corky. Leaves alternate, simple [rarely compound], often of floral-tube as 1–7 [–ca. 15] series of filaments or outgrowths, sometimes membranous; extrastaminal nectary disc often present; stamens [4–] 5 [–ca. 25], usually borne on androgynophore [hypanthium]; ovary superior, [2–] 3 [–5] -carpellate, 1-locular, usually borne on androgynophore; placentation parietal; styles distinct [variously connate]; stigmas capitate or clavate to reniform, sometimes 2-lobed [fimbriate]. Fruits baccate or capsular. Seeds (1–) 3–ca. 200, arillate, usually compressed, surface usually pitted to reticulate or grooved.

Distribution

Nearly worldwide, primarily in tropical regions, especially South America and Africa

Discussion

Genera 17, species ca. 750 (1 genus, 18 species in the flora).

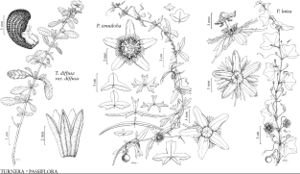

Passifloraceae have been historically assumed to be closely related to Achariaceae, Caricaceae, Cucurbitaceae, Flacourtiaceae, Malesherbiaceae, and Turneraceae (A. Cronquist 1981); they are currently considered to be most closely related to the latter two families, seated within Malpighiales (D. E. Soltis et al. 2000; M. W. Chase et al. 2002; Angiosperm Phylogeny Group 2003; N. Korotkova et al. 2009). All three families have cyanogenic compounds, flowers with a hypanthium often not bearing the stamens, a floral corona (although uncommon in Turneraceae), tricarpellate ovaries with three elongate styles, parietal placentation, and five stamens (Cronquist; Angiosperm Phylogeny Group). Because of the close relationship of these three families, they have recently been treated as an expanded Passifloraceae (Chase et al.; Angiosperm Phylogeny Group). Passifloraceae are still considered relatively closely related

to members of the now ex-Flacourtiaceae, particularly Salicaceae in the broad sense (Chase et al.), which includes the apparently corona-bearing Abatia Ruiz & Pavón (coronal filaments in Abatia, unlike those in Passifloraceae, are clearly staminal appendages; see A. Bernhard 1999), although the members of Flacourtiaceae that have cyanogenic compounds are possibly more distantly related to Passifloraceae and are now placed in a greatly expanded Achariaceae (Chase et al.). The family description provided above represents Passifloraceae in the narrow sense; Malesherbiaceae and Turneraceae are not included.

Passifloraceae are divided into two tribes: Passifloreae de Candolle, containing genera with tendril-bearing vines and scandent shrubs (or rarely small trees without tendrils), and Paropsieae de Candolle, containing genera without tendrils that are shrubby or arborescent (W. J. J. O. de Wilde 1971). Paropsieae have been assigned to Flacourtiaceae or are seen as transitional between Flacourtiaceae and Passifloraceae (de Wilde). Morphological evidence supports the inclusion of Paropsieae within Passifloraceae (E. S. Ayensu and W. L. Stern 1964), further supported by recent molecular phylogenetic evidence (D. E. Soltis et al. 2000; M. W. Chase et al. 2002). Beyond this, intergeneric relationships are largely unknown within Passifloraceae. The tribes may not be distinct as currently defined and some genera are probably derived from within Passiflora (that is, Hollrungia K. Schumann and Tetrapathaea (de Candolle) Reichenbach; S. E. Krosnick and J. V. Freudenstein 2005).

The floral corona of Passifloraceae is of uncertain origin, considered derived from the perianth (V. Puri 1948) or consisting of staminodes (P. K. Endress 1996). It has an unusual pattern of development, inward from the outer and inner margins of a ringlike primordium; its development is delayed until well after the fertile stamens begin to form; and the arrangement and number of coronal filaments is not consistent with that of the fertile stamens. There is little support for the corona being derived from perianths or staminodes (A. Bernhard 1999).

Selected References

None.